Celebrating Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

I am celebrating my 50th birthday this month. If you ask me when I was born, I will tell you May 22, 1973, since it is in all of our legal documents and when my umma (mom) entered the birthing center. If you ask her, she will tell you May 23rd, which is the day I was actually born. I was born in Busan, South Korea. Busan was the second largest city in South Korea, back in the 1970s. Korea was led by an autocrat and was only 10 years into being an industrialized nation, it had not yet, become the BTS and K‑Beauty industrialized country it is today. It was poverty-stricken and my ahpa (dad) dreamed of immigrating to the land of plenty — America.

Being born in another country and then raised in a different country, I was a confused kid. I didn’t look American but I didn’t feel Korean and I was usually mistaken for being Chinese — a common stereotype being “all Asians looked alike”— we got clumped together as being Chinese.

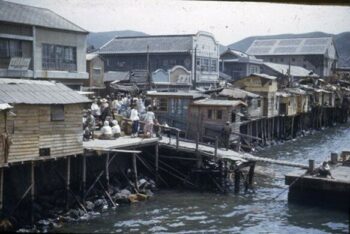

Busan, South Korean in the 1970s

I was a latchkey kid because my parents worked all the time and sometimes if they worked on the weekends, the library and librarians were our babysitters. (This would not happen anymore, but it was what our family needed to do.) I learned what to say when asked where my parent was or if we had a curious and caring librarian ask to see them, my brother and I would leave, wander the neighborhood, and then come back later. The librarians didn’t notice that we were the same kids because “all the Chinese kids look alike” and we went to a library where there were a decent number of Asian families. When we wandered the neighborhood, white kids (usually boys) riding their bikes would chase my brother and me yelling “chink” and other expletives, but we would just ignore them because we thought they were stupid because we were Korean, not Chinese. There were also times I would call them stupid and then get beat up. (My brother, still a very tolerant and kind soul, was not a fighter and would be annoyed that he would have to run or get into fights because of my “big” mouth.)

Gamcheon Culture Village, Busan, South Korean. After being revitalized in 2009, this former slum is now known as the ‘Machu Picchu of Busan’.

In junior high, I wanted to be Jewish. I grew up in Morten Grove, Illinois, where I was attending a Bar/Bat Mitzvah celebrations every weekend. I loved the Jewish culture and thought the rite of passage to adulthood was such a “cool” tradition. When we immigrated, my parents wanted us to acculturate and assimilate into American culture. My paternal grandfather died shortly after we moved to our new house in Morten Grove. I remember the shrine we made for my grandfather, whom I don’t remember ever meeting, but I also remember creating and honoring his death each year (called a Jesa) and one year we didn’t. Looking back, maybe it was part of the acculturation, maybe it was my parents got too busy, or maybe because it was only us and usually family gets together to honor our departed loved ones.

In high school, I finally embraced being Korean and American. I joined the Korean Club, attended Korean church and was active in student government (something my mom thought was very American to do). It wasn’t until college I finally understood my identity — being Korean American. I realized the best part of me was that I am born with the history and blood of a resilient people. Fun fact, depending on the source, Korea has been invaded by other countries trying to occupy or annex it throughout history over 20 times and each time Koreans fought back. Even during the Japanese Occupation of Korea (1910−1945) when the Japanese attempted to wipe out Korea’s culture and language — my people fought back. My maternal grandparents were teachers in Korea and were given Japanese names and told only to speak Japanese, which they were fluent. Although I don’t know all the history, my Oehal-abeoji (maternal grandfather) was also part of a university demonstration against the Japanese occupation.

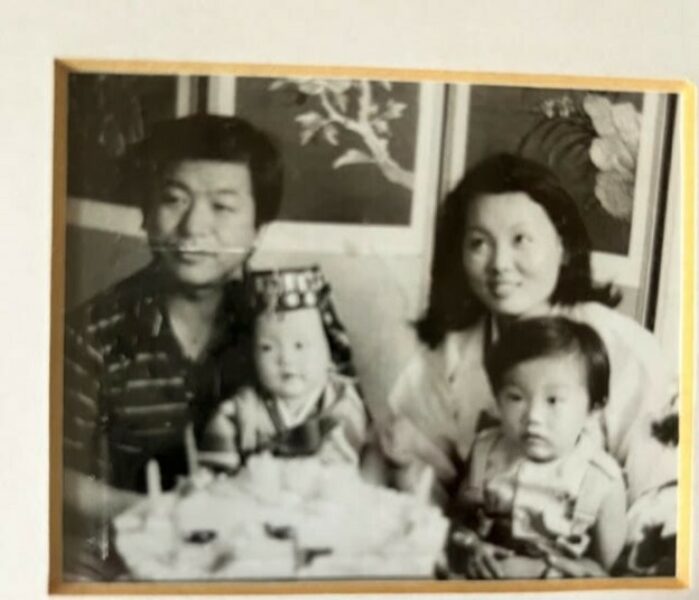

My first birthday—in Korean—it’s called “dol” or “doljanchi.” I know it’s my first birthday since I am wearing a Hanbok and it’s very significant in telling a baby’s future prosperity. Also, this is one of the only 2-3 pictures of me as an infant. I have these and then I’m in grade school.

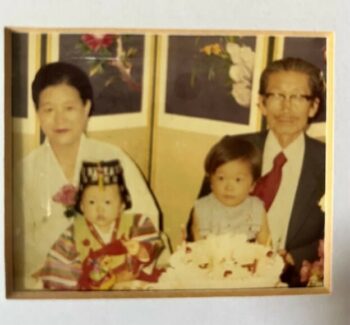

My paternal grandparents. I remember my Halmeoni (grandmother); she came to live with us for a little while when I was in grade school. She was the best. Also pictured is my Hal-abeoji (grandfather) and I referenced above.

Leading back to Asian American and Pacific-Islander History Month, for me, it’s about remembering where I came from and what my parents endured to get my brother and I to the United States. In retrospect, while it was hard on everyone, the greatest negative impact was felt by my mom. She was uprooted from her sisters with whom she was very close and then thrown into a truly foreign and unwelcoming world. The life of an immigrant could be very isolating and lonely, especially if a family is not joining relatives already established in the States. I still think she feels the impact of this isolation, loneliness, and missing her family. Remembering and learning more about my culture helps shape my identity as a proud Korean American, so my children can also embrace who they are, and be proud to be Korean American and part of the larger AAPI community.

Learning about AAPI history in the United States allows me to remember that AAPIs have helped build America. We are not a disease, or a foreigner, or a scapegoat. Fortunately for those living in IL and with school-age children, in July 2021, Illinois was the first state to require all public schools to make Asian American history part of the curriculum. But I would also like to add that learning AAPI history, when done with intention, will be wonderful and eye-opening. I would caution that those learning it should also be aware that those teaching it may still carve out what someone doesn’t want taught. We do not want AAPI history to be used as a wedge against other marginalized communities. What is best is when AAPI history is taught alongside with African American/Black history or other communities’ histories and a full picture of American history can be understood.

Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Facts

- 1765: Filipino sailors, known as “Manilamen” were indentured servants on Spanish ships. They jumped ship and established Filipino American communities in the bayous of Louisiana.

- From 1863 – 1869, roughly 15,000 Chinese laborers built 90% of the Transcontinental Railroad on the western front.

- 1963: The brief but lasting friendship between Malcolm X and Yuri Kochiyama — While many know Malcolm X, Yuri Kochiyama and her family were sent to an internment camp from California to Alabama, where she saw the racism faced by Black Americans in the Jim Crow South. Later in life, she moved to New York, and as a mother of six children, was active in the civil rights movement and held great admiration for Malcolm X. It was there that they met and bonded, and she continued her fight for social justice and human rights. “Kochiyama bridged people and movements, a true human rights activist.” (zinnedproject.org)

This is just a small glimpse of AAPI history and what richness the AAPI communities have brought to the United States.

Some resources to learn more about AAPI Heritage and History: The Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, Wing Luke Museum, and Yuri Education Project. Co-founder, Freda Lin, is a dear friend and was my roommate in college — freshman and senior year.

May is Asian American & Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, which is a time to recognize, uplift, and honor the contributions that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have made both historically and culturally. KYC is proud to celebrate our Asian American and Pacific Islander staff members, clients, and community members, this month and year round!

Previous Article Next Article