Shifting the Power on National Coming Out Day

Written by: Donna B., LGBTQ+ Center Project Lead

Special acknowledgements to the Q+ Crew for being bold baddies, our outspoken allies for lifting us up, and anyone out there who has ever wondered if there’s anyone else out there.

This coming Monday, October 11th marks 33 years of celebrating National Coming Out Day, a celebration in which LGBTQ+ people are called on to “come out of the closet” in the name of advancing visibility. In honor of this groundbreaking day for the community and of the innovative strategies that Kenneth Young Center implores in its advocacy for LGBTQ+ people, I ask you to ponder this question: should “coming out” as LGBTQ+ still be the goal for achieving equity?

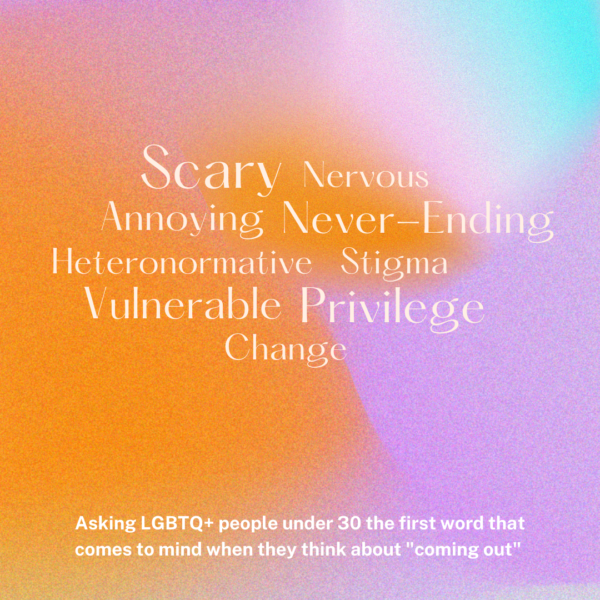

I asked some LGBTQ+-identified friends (all of whom are under 30) the first words that came to their mind when they think of the action of “coming out.” These are the words they used:

Some of you might be perplexed by this, maybe because the narrative has been that LGBTQ+ people must feel relieved, liberated, and empowered by the action of coming out. Of course, “the action” and “the result” are two separate matters; sometimes, things don’t feel good as we do them even though the consequences benefit us (eg: why I turned off social media notifications). But why do we revere an action that elicits such negative emotions to the very people that it’s meant to alleviate, and is there a better way? Perhaps, it’s a matter of words.

Coming Up with “Coming Out”

In the United States, the phrase “coming out” dates back on record to the early 20th century as a term originally used in the context of “a woman coming out as a débutante,” meaning that she was old enough to be married. Following the blossoming gay culture of the experimental Roaring 20s, the depressive 30s brought about an era of intense anti-gay rhetoric and violent oppression. It was then that a 1931 Baltimore newspaper referred to a gay gathering as a “Pansy Ball” featuring “the coming out of new debutantes into homosexual society,” a play on words intended to disgrace men for acting like women.

By the 1960s and 70s, LGBT activists were reclaiming the phrase “coming out,” using it as a code word to identify people “in the family”, when for safety reasons these things couldn’t be openly discussed. An organizer at the first gay liberation march in 1970 said “we’ll never have the freedom and civil rights we deserve as human beings unless we stop hiding in closets and in the shelter of anonymity.” Thus, the link between coming out and hiding in the closet was explicitly joined. By the end of the 70s, the two ideas became synonymous as evident in Gay politician Harvey Milk’s famous quote: “If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door,” (a presentiment that would sadly come true in the following months).

Knowing this history, it’s obvious that “coming out of the closet” is inherently rooted in the moralistic idea that LGBTQ+ people who do not openly disclose to their friends, relatives, and coworkers that they are LGBTQ+, are hiding something, most likely out of shame and fear, and at the detriment to themselves and other LGBTQ+ people. It’s a catch 22: if you come out, you’ll likely face stigma and discrimination, and if you don’t, you’re further proving that there is something to be ashamed of.

Flipping the Switch

Let’s explore the question of what we can do, or say, that advances the spirit of National Coming Out Day while recognizing the unfair burden it places on LGBTQ+ people.

A few years ago while at a conference, I met a group of LGBTQ-identified Muslim youth from a group called MASGD who presented a phrase which I actually felt liberated by. The term they used was “inviting in,” as in LGBTQ+ people have the autonomy to choose with whom in their life they invite in to know about their identities, removing the pressure of public disclosure and feelings of being a “bad queer person” for not being “out” in every circle. This wording changed my life. Even the imagery of the phrase gives me a visceral reaction: in one world view, I’m alone, in a cold, dark, crypt-like space, wondering if it’s worse to stay inside until the oxygen depletes or step into the blinding brightness to an unknown environment, over and over, everywhere I go, for as long as I live. In the other, I see myself in a cozy-lit room, very familiar to me, sharing some hot tea (both meanings) with friends, content, safe, and everywhere I go people knock on my door, but ultimately I hold the power to assess them through the peephole and decide if they are company worth keeping.

I asked my same friends from the beginning what they felt about the action of “inviting in,” and this is what they shared:

- “Powerful”

- “I like it”

- “Welcoming”

- “Proud”

- “Warm”

And:

- “What does that mean?”

- “Never heard of it!”

Want to share your support for LGBTQ+ folks in honor of National Coming Out Day? Copy and share the image above to post on social media! Here's a suggestion of what to share in your post along with this image:

In honor of National Coming Out Day on October 11th, I recognize that publicly “coming out” can be difficult and may not be safe or comfortable for everyone.

Instead of “coming out”, what if we “invite in” others to our authentic selves? Check out this blog to learn more: https://www.kennethyoung.org/b...

#NationalComingOutDay #LGBTQIA+ #TogetherWeThrive #WeAreKYC #InvitingIn

Upon further explanation of the term, which is likely new to most, a friend told me “I’ve never heard that terminology before, but I think the phrase itself makes me feel a lot less secretive… Now that I think about it, years later after coming out, I did feel like I was hiding this huge secret that I felt like I needed to share with everyone for their own comfort… when it should have been me waiting to tell whoever I wanted to tell for my own comfort.”

What if, on this year’s National Coming Out Day, we placed the accountability of “coming out” on our cisgender and straight allies? Does the idea of having to vocalize to your friends and family that you support LGBTQ+ people make you nervous, and if so, does it make you think twice about what actual LGBTQ+ people experience on a daily basis? What would it do for queer people all over the world to see their neighbors, teachers, siblings, parents, bosses, doctors, and leaders come out against the phobias and ‑isms that make us feel isolated and invisible? How would it mobilize efforts for equity if those with privilege said “I want to become someone worthy of knowing you, someone whom you can lean on”?

We don’t know what we stand to gain together until we’re in this together, and I invite you to imagine the possibilities with me.

KYC’s LGBTQ+ Resources

Kenneth Young Center offers a range of supportive services to LGBTQ+ individuals and families. If you or someone you know is looking for compassionate behavioral health support, contact our team at 847−524−8800.

We also offer our LGBTQ+ Youth and Young Adult Center, a resource for youth to explore their authentic identities and find community. We offer a variety of activities and resources throughout the year. Click here to learn more about our LGBTQ+ Center.

KYC is honored to highlight 50 stories, events, and programs that capture the depth and breadth of our services during our 50th anniversary year through our #KYC50For50 campaign.

Previous Article Next Article